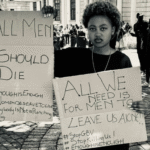

#ME_TOO_2025

South Korea says it wants gender equality. Its criminal code says otherwise.

Under Article 297, rape is defined as “sexual intercourse by means of violence or intimidation.” In other words, the law still demands that victims prove they fought back. That’s not a legal standard. It’s a survival test.

For years, survivors have said the same thing: the law protects abusers, not women. Each case ends the same way “insufficient evidence of resistance,” “no physical injuries,” “consensual ambiguity.” Judges dissect bruises like they’re policy documents. Prosecutors still ask why she didn’t scream. Lawmakers promise reform, then look away once the cameras cut.

But silence has an expiration date.

The Law That Time Forgot

South Korea’s sexual violence statute hasn’t caught up with international norms. Countries like Sweden, Spain, and even Japan now define rape based on the absence of freely given consent, not on the presence of force. Korea’s law still operates on the assumption that sex is legal unless a woman can prove a violent interruption. That’s not consent, that’s coercion disguised as culture.

The #MeToo wave cracked that wall open in 2018. Politicians resigned, prosecutors fell, and women started speaking. But the law itself didn’t move. Legal reform proposals gathered dust in the National Assembly while lawmakers debated “moral consequences.” In the meantime, survivors kept reliving their trauma in cross-examinations written by men who think compliance equals consent.

The Cultural Trial

In South Korea, shame travels faster than justice. Victims face public humiliation, professional exile, and digital smear campaigns. The burden of proof isn’t just legal, it’s social. When the case ends, the woman’s life usually does too, at least in public terms.

Activists say it’s not just about rewriting statutes. It’s about dismantling the cultural idea that a woman’s no must sound like a war cry. The government’s slow pace reflects something deeper: fear. Fear that a new standard of consent will expose how much of Korean society still romanticizes male control and female silence.

The Justice Ministry’s 2025 reform committee has floated a “consent-based” revision. Draft language frames sexual assault around “lack of voluntary agreement.” Critics, mostly conservative lawmakers call it a “Western import” that threatens traditional values. Translation: they fear accountability.

Human rights lawyers argue that the reform isn’t radical. It’s overdue. South Korea ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) decades ago. Under that treaty, it already has a duty to align its domestic laws with the principle of equality before the law. The constitution promises dignity and bodily autonomy; the penal code hasn’t gotten the memo.

Legally, the pivot from “force” to “consent” changes everything. It shifts the presumption of agency back to the victim. It modernizes evidentiary standards, allowing psychological coercion, imbalance of power, or intoxication to qualify as lack of consent. It tells judges that sex without agreement is not a gray zone, it’s a crime.

But reform without enforcement is theater. South Korea can’t just legislate equality; it has to practice it. Training prosecutors, rewriting judicial guidelines, and changing police protocols will matter as much as the amendment itself.

For every survivor still waiting for justice, the legal code is personal. It decides whether her story becomes a case or a cautionary tale. When the law says violence must be visible, pain that isn’t seen is never believed.

Almost 2026, and women are still demanding the right to say no, and to have it mean something.

The law can’t keep pretending not to understand.

Author

Latest entries

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-23When the Violence Ends, Another Battle Begins: Why Mental Health Must Be Part of GBV Policy

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-23When the Violence Ends, Another Battle Begins: Why Mental Health Must Be Part of GBV Policy Women ♀️2025-11-22South Africa Declares Gender-Based Violence a National Disaster While Its Women Silenced The Country

Women ♀️2025-11-22South Africa Declares Gender-Based Violence a National Disaster While Its Women Silenced The Country  Lex Feminae Index2025-11-21Gender Base Violence — 16 Days of Activism BUT 365 Days of Violence

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-21Gender Base Violence — 16 Days of Activism BUT 365 Days of Violence Lex Feminae Index2025-11-12Women’s Rights: Help Was Sent Then The Help Raped

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-12Women’s Rights: Help Was Sent Then The Help Raped