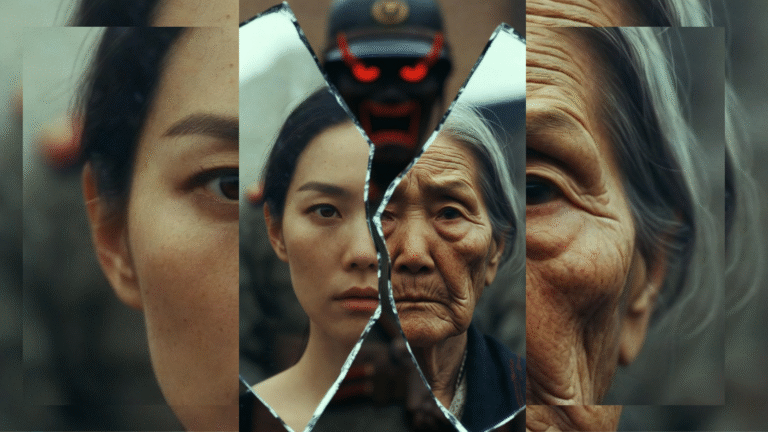

When the Violence Ends, the Battle Begins: Why Mental Health Must Be Part of GBV Policy

Gender based violence does not end when the bruises fade. It continues in the mind, in the nervous system and in the parts of life survivors are expected to simply “move on” from. The law recognizes GBV as a crime. Health systems recognize trauma as a disorder. Yet neither fully responds to the way these two realities collide inside a survivor’s life.

Globally, more than one in three women experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime. Many also face long lasting psychological harm including post traumatic stress, depression, chronic anxiety, and increased risk of suicide. Mental health is not a secondary issue. It is one of the primary consequences of the violence itself.

Policy too often treats mental health like a separate chapter, something handled later through counseling or medication. Survivors know better. The fear that follows an assault can rewrite a life. It affects a woman’s ability to work, study, parent, trust, sleep, or feel safe in her own home. If the legal system focuses only on the crime scene and not on the mind that survived it, then the state has not provided justice. It has provided paperwork.

International human rights law already tells governments what they owe survivors. Under CEDAW, states have a duty to prevent gender based violence and ensure adequate health services for those affected. The right to the highest attainable standard of mental health is protected under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. These are not guidelines. They are binding commitments. They require systems that protect both the body and the dignity of those harmed.

Yet survivors still face barriers that are policy choices, not inevitabilities. Reporting rape can trigger police skepticism, public humiliation and court delays. Many women are forced to relive the worst moments of their lives without mental health support in place. Others are told to “prove” the impact of trauma to qualify for services. When a state’s response becomes another source of harm, the violence has simply changed hands.

Jessica Ingrée

Prevention must also include mental health. Programs that reduce alcohol abuse, address toxic masculinity, and support early intervention in abusive relationships have proven benefits. When countries invest in trauma informed policing and survivor centered legal processes, reporting increases and repeat violence drops. These results show that reform is not only possible. It is urgent.

Survivors are not cases. They are citizens. They deserve policies that help them rebuild control over their lives. That means free and confidential mental health care, long term protection orders that are actually enforced, financial support to prevent dependence on abusers, and training for every professional who may be a survivor’s first point of contact. GBV is a public health emergency and the mental health fallout is a measurable, preventable consequence.

We cannot call a system fair when it waits for survivors to be strong enough to ask for help. A just system recognizes trauma before trauma has to introduce itself. The real test of any state is simple. Does the system protect her after she survives. Until that answer is yes, policy has more work to do.

Author

Latest entries

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-23When the Violence Ends, Another Battle Begins: Why Mental Health Must Be Part of GBV Policy

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-23When the Violence Ends, Another Battle Begins: Why Mental Health Must Be Part of GBV Policy Women ♀️2025-11-22South Africa Declares Gender-Based Violence a National Disaster While Its Women Silenced The Country

Women ♀️2025-11-22South Africa Declares Gender-Based Violence a National Disaster While Its Women Silenced The Country  Lex Feminae Index2025-11-21Gender Base Violence — 16 Days of Activism BUT 365 Days of Violence

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-21Gender Base Violence — 16 Days of Activism BUT 365 Days of Violence Lex Feminae Index2025-11-12Women’s Rights: Help Was Sent Then The Help Raped

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-12Women’s Rights: Help Was Sent Then The Help Raped