South Korea’s Cho Doo-soon Case: An 8-year-old Sexually Assaulted

By The General Justice Lawyer, June 1

The year is 2008. Ansan’s Cho Doo-soon sexually assaulted an 8-year-old girl, receiving a 12-year sentence that sparked nationwide outrage in South Korea.

The “violence and intimidation” rape law’s narrow scope, which required proof of coercion, fueled protests demanding consent-based reforms. The case’s shock drove legislative change, but the fight for broader protections persists.

On a December morning in 2008, Cho Doo-soon abducted an 8-year-old girl, known as “Na-young” in media to protect her identity, from a church bathroom in Ansan, Gyeonggi Province.

He brutally raped her, leaving her with permanent physical and psychological injuries. The trial revealed chilling details: Cho’s intoxication was cited as a mitigating factor, and the court sentenced him to just 12 years, far below the life imprisonment many expected.

South Koreans, stunned by the perceived leniency, flooded the streets, their protests amplifying a national reckoning over sexual violence laws.

South Korea’s rape law at the time defined rape as requiring “violence and intimidation,” meaning prosecutors had to prove physical force or threats, not merely lack of consent.

In Cho’s case, the law’s narrow scope allowed his intoxication defense to reduce the sentence, as it was argued he lacked full intent.

Legal scholars criticized this standard for failing to address consent or protect vulnerable victims, like children.

The Cho Doo-soon case, alongside later cases like Ahn Hee-jung’s 2018 trial, exposed how the law often favored perpetrators over survivors, igniting calls for a consent-based framework.

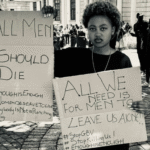

The Nation’s Response was loud. The public’s fury led to immediate action. Protests in Ansan and Seoul drew thousands, with parents and activists demanding harsher penalties and better victim protections.

Social media helped amplified the outcry, with hashtags like #NaYoungCase trending.

A mother from Ansan, who joined the protests, shared her fear:

“I couldn’t let my daughter walk to school alone after that. We needed change.”

Her story echoed countless others, uniting communities in grief and resolve.

The 2010 “Cho Doo-soon Law”

In response, South Korea passed the 2010 “Cho Doo-soon Law,” mandating electronic anklets for convicted sex offenders post-release to track their movements. This was a direct outcome of the case, aimed at preventing recidivism.

However, critics argued it didn’t address the root issue: the legal definition of rape. While the law marked progress, it fell short of the consent-based reforms activists sought, leaving gaps in survivor protections.

The Cho Doo-soon case fueled a broader movement for rape law reform, influencing later #MeToo protests in South Korea, particularly after the 2018 Ahn Hee-jung case.

In 2022, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family proposed redefining rape as non-consensual sex, but the plan was canceled in 2023 amid political shifts. The case’s legacy endures, with activists citing Na-young’s story to push for systemic change, though progress remains stalled.

The General Justice Lawyer

Independent Reporter

Follow @genjustlaw on X

Author

Latest entries

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-23When the Violence Ends, Another Battle Begins: Why Mental Health Must Be Part of GBV Policy

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-23When the Violence Ends, Another Battle Begins: Why Mental Health Must Be Part of GBV Policy Women ♀️2025-11-22South Africa Declares Gender-Based Violence a National Disaster While Its Women Silenced The Country

Women ♀️2025-11-22South Africa Declares Gender-Based Violence a National Disaster While Its Women Silenced The Country  Lex Feminae Index2025-11-21Gender Base Violence — 16 Days of Activism BUT 365 Days of Violence

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-21Gender Base Violence — 16 Days of Activism BUT 365 Days of Violence Lex Feminae Index2025-11-12Women’s Rights: Help Was Sent Then The Help Raped

Lex Feminae Index2025-11-12Women’s Rights: Help Was Sent Then The Help Raped